Spotlight on PD in Connecticut: Focus on Yale

Note: This is the first in a series highlighting what’s happening around Connecticut in the area of Parkinson’s research, treatment, innovation, and collaboration. We will highlight a different entity each month.

It’s a rainy Tuesday at Yale this 29th day of October, with a multitude of activities happening all over campus; students, faculty, researchers, plus Yale New Haven Health, street vendors, patients, and so much more. It truly is a bustling environment, with everyone around campus seemingly dialed in on what they need to be doing, where they are going, and all moving at a very rapid pace: work to be done, classes attended, appointments kept.

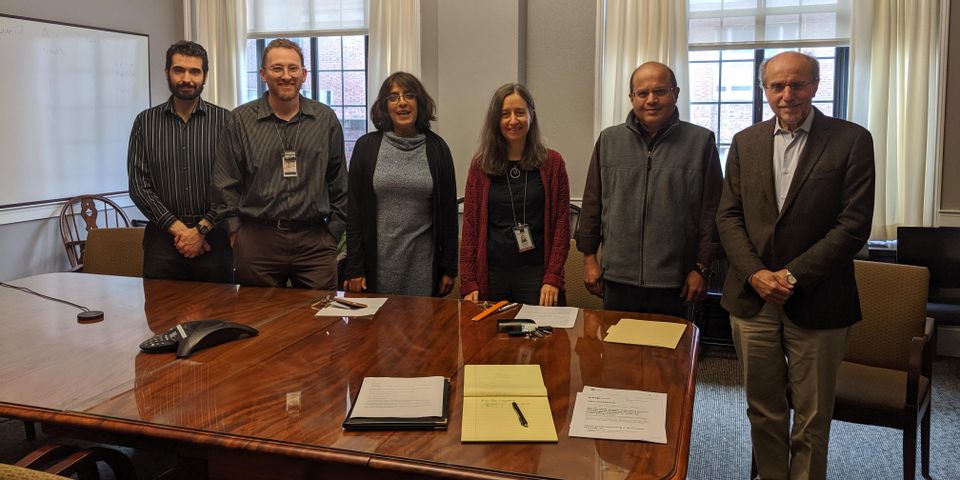

Yet here in an upstairs conference room at the Yale Medical School, a variety of Yale researchers, faculty, professors, and administrators took time from their busy days to share with me – and by extension, you, the CAP audience - one of their passions: finding answers to the puzzle known as Parkinson’s disease.

The overarching sense I got when talking with the Yale team was purpose: a burning desire to answer questions that can lead to useable and meaningful outcomes. From answers in basic science to answers in translational and clinical research, the clear need identified was to find answers – and then use them for the common good.

First, a primer.

“Whereas basic research is looking at questions related to how nature works, translational research aims to take what’s learned in basic research and apply that in the development of solutions to medical problems. Clinical research, then, takes those solutions and studies them in clinical trials. Together, they form a continuous research loop that transforms ideas into action in the form of new treatments and tests and advances cutting-edge developments from the lab bench to the patient’s bedside and back again”.[1]

Back to our gathering. Dr. Pietro De Camilli is the Chair of the Department of Neuroscience at Yale Medical school, and he immediately speaks of the tremendous strength of Yale in the areas of molecular biology, cell biology – among others – and how those strengths are important to all three areas – and in having an impact.

Dr. De Camilli is a founding member, together with Dr. Elan Louis, Chief, Division of Movement Disorders, of the internal group known as “YPDRG”: Yale Parkinson’s Disease Research Group. (The group gathers informally to promote internal collaboration, information sharing, and best practices).

De Camilli also speaks of his and Yale’s participation with the ASAP initiative (Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s) and the incredible potential this fledgling (3 years) effort can have on PD research. It’s heady stuff, and it involves areas that CAP has taken a strong position on: collaboration, creativity, flexibility, and transparency. (ASAP is managed by the Milken Institute). While the discussion is sometimes highly technical, the theme is crystal clear: basic science matters — big time. And Yale is doing just that – with a great team.

Part of that great team is Sreeganga Chandra, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Neurology and Neuroscience; Associate Professor, Neurology; Associate Professor of Neuroscience; Deputy Chair of Neuroscience. She joins us at the conference table, and her laser focus is evident: foundational, basic science. Get the answers, and so much can emanate from those answers. The team clearly works well together, and Chandra is obviously an integral part of it. Her mention of basic science rings true with other team members, and they echo her sentiment that basic science requires patience, support, resources – and should be valued by patients and scientists alike. It is foundational in nature and a prerequisite to truly successful outcomes. (She is also co-chair of the Yale PD symposium being held in April; more on that under separate cover).

Sitting next to Chandra is Dr. Sule Tinaz, MD, Ph.D., Assistant Professor at the Yale School of Medicine, and clinical researcher. Dr. Tinaz has worked with CAP in recent years and was instrumental in bringing the group together to share their passions and ideas. She shares hers in her clear, authentic manner that makes it easy for the writer to understand why she is so interested in her clinical research: to help patients. Plain and simple, she wants PWP’s to live lives that, in the short term, have as few complications as possible, and she aims to get there with meaningful research about things that are directly applicable to PWP’s today: brain plasticity and exercise. Her emphasis on non-pharmacological research rings true with CAP as it dovetails with CAP’s emphasis on exercise and wellness. Tinaz’ message comes through loud and clear: there can be no answers if clinical trials do not reach full participation, and hers at present need many more participants. (Note to readers with PD: clinical trial volunteers/participants sorely needed. Please help!)

Also trying to find answers through clinical research is Dr. David Matuskey, MD, Assistant Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging and of Psychiatry and of Neurology; and Medical Director, Yale Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Center. Dr. Matuskey’s expertise in, and passion for, PET, and using it to find answers, is infectious. His is a quest for clarity: using radioactive isotopes that bind to specific things in our brains over very short time frames that are then measured in a PET scan (as one example). As we tour the Yale PET Center, the equipment is impressive, but the dedication of Dr. Matuskey and his team to the quest for answers, and the need for highly accurate systems that deliver measurements that are critical to neurological research is the real highlight.

Part of Dr. Matuskey’s team is Mark Dias, research coordinator who is responsible for a variety of different studies utilizing different patient groups and healthy control and contacting, screening, and assessing subjects for different MRI and PET scan-based studies. When asked, Mark humbly, but energetically mentions that his work truly is a passion and has a purpose. This isn’t just a job to Mark, it’s a way to move forward in the quest to find answers and contribute in a meaningful way to getting meaningful, useful results that can be used to build steps to DMT’s and a cure. Clearly, there is “soul” to his “role,” and that applies to the entire team that was interviewed.

As a sports fan, our final conversation was one that had additional relevance based on recent events. Anyone that knows the names Billy Bean, Theo Epstein, or the new Red Sox executive, Chaim Bloom, knows that the common theme there is analytics. As we conversed with Hemant Tagare, Ph.D., Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging and Biomedical Engineering, it became quickly apparent that unlocking the mysteries of Parkinson’s will undoubtedly include analytics. The fascinating part of that statement is not the use of the large data sets, but of the ability to extract meaningful, and ultimately useful, patterns, trends, and high-gain results that can have an impact in a variety of ways. Example: by finding correlations in data that have a high enough rate of statistical significance, some very expensive tests can become unnecessary. Not only a tremendous money saver but a time and resource saver as well.

Hemant’s ability to gain deep insights into the PD test data, by putting together algorithms that are unique to data sets, is truly something that sets this group apart: not only is their research and data gathering happening, but Hemant is involved, in what he calls “deeper insight into fundamental problems” – trying, via analytics, for the high-gain result that just might be that nugget of data that can aid in bringing disease-modifying treatments – and ultimately, a cure.

[1] https://blog.dana-farber.org/insight/2017/12/basic-clinical-translational-research-whats-difference/

About the Business

Have a question? Ask the experts!

Send your question